This year’s 75th anniversary of the voyage of the refugee ship St. Louis coincides almost exactly with the 100th anniversary of the birth of a long-forgotten Dutch playwright who actually used the story of the ship to help save Jews from the Holocaust. It’s an amazing chapter of history that is, sadly, almost completely unknown to the public.

The St. Louis, with 930 German Jewish refugees aboard, set sail from Hamburg on May 13, 1939, bound for Havana. Cuba was one of the few countries left that was willing to accept Jews fleeing Hitler. Or so it seemed.

In the face of growing public opposition to immigration, Cuban president Laredo Bru decided at the last moment to cancel the entry visas that the St. Louis passengers were holding. The ship waited in the Havana harbor as American Jewish emissaries negotiated with Cuban officials over the passengers’ fate.

Some of the passengers’ relatives had reached Cuba earlier. As theSt. Louis idled in the harbor, they boarded small boats that took them closer to the ship, to shout messages of encouragement and catch a glimpse of their loved ones.

When it became clear that Cuba would not admit the passengers, the St. Louis, which The New York Times called “the saddest ship afloat,” sailed north to the coast of Florida. It hovered there for three days.

The passengers sent a telegram to the White House, pleading for mercy and emphasizing that “more than 400 [of the refugees] are women and children.” The reply came in the form of a Coast Guard cutter, which was dispatched to the scene to make sure the St. Louis did not come closer to America’s shore.

Refuge Denied

Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. proposed that the passengers be granted temporary haven in the U.S. Virgin Islands. As a territory rather than a state, the Virgin Islands was not subject to the regular immigration restrictions. But President Roosevelt rejected the idea of using the islands as a haven, on the grounds that Nazi spies disguised as Jewish refugees might sneak from the Caribbean into the mainland United States.

The St. Louis slowly sailed back toward Europe. A Nazi newspaper, Der Weltkampf, gloated: “We are saying openly that we do not want the Jews, while the democracies keep on claiming that they are willing to receive them – then leave them out in the cold.”

Before the ship reached Europe, the governments of England, France, Belgium, and Holland each agreed to accept a portion of theSt. Louis passengers. The refugees who were admitted to Holland were held behind barbed wire in a detention facility called Westerbork.

While grateful not to be returned to Germany, the passengers understood they were still in the middle of a danger zone. Researchers from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum interviewed one former St. Louis passenger who was sent to France and then quickly departed for Hungary because, as he put it, “After all, people knew the Nazis could invade France at any time.”

For the same reason, passenger Michael Fink and his parents, who were sent to Holland, immediately applied to become construction workers in Chile. Warren and Charlotte Meyerhoff, who were also taken to Holland, smuggled themselves out of the Westerbork facility and made their way back to Cuba.

Symbol of National Pride

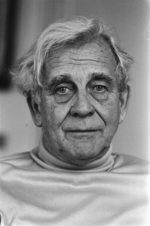

The St. Louis approached the Dutch shore on the afternoon of June 18. A small steamer, the Jan van Arckel, pulled alongside and took 181 passengers into the port of Rotterdam. Like most of his countrymen, 25-year-old Jan de Hartog, the skipper of a tour boat on the Amsterdam Canals, had closely followed the news of the dramatic voyage of the refugee ship.

The son of a Dutch Calvinist minister, de Hartog was raised in the northern Dutch city of Haarlem. (In honor of their hometown, early Dutch settlers named upper Manhattan “Nieuw Haarlem.”) From an early age he exhibited a love for the sea, and even ran away at age 11 to become a cabin boy on a Dutch fishing trawler. In early 1940, de Hartog produced and starred in a film about the Dutch navy, “Somewhere in Holland.”

At almost the same time, his first novel appeared: Holland’s Glory, which depicted the life of Dutch sailors in striking and glamorous terms, was published just days before the German invasion of Holland in May 1940. The novel became an instant bestseller and de Hartog became a living symbol of Dutch national pride.

“People put the book in their windows with the title facing outward, with candles by the side,” he later recalled. “There were stacks of the books in the shop windows of butchers and haberdashers who had never displayed a book before.” More than half a million copies were sold.

The German occupation authorities regarded de Hartog as a threat. They banned the book and the film on the grounds that they were arousing “national passions,” and de Hartog went into hiding to avoid arrest. At one point he lived in an old age home, disguised as an elderly woman.

“The Dutch film studios were closed, and everybody connected with them was thereby officially unemployed and liable to be deported to Germany as slave labor,” de Hartog recalled many years later, in a talk at Weber State College in Maine.

“We decided to go underground and form the ‘Underground Theatre,’ which would travel through the country and perform in barns and haylofts and, in the case of the Zuider Zee [the famous Dutch bay], in those large sheds where the fishermen dried and mended their nets. As we thought it was too dangerous for women, we decided it would have to be a play for men only. Of course that was a silly conclusion; as it turned out the women were much better at underground activity than the men, but that’s another chapter.”

Searching for Hiding Places

In the summer of 1942 the Germans began preparations for the mass deportation of Dutch Jews to Auschwitz. On July 6, Anne Frank and her family went into hiding in an Amsterdam attic. Themselves refugees from Germany, the Franks were undoubtedly well aware of what happened to the St. Louis. In fact, Anne’s mother, Edith, wrote to a friend in 1939: “I believe that all Germany’s Jews are looking around the world, but can find nowhere to go.”

Before the war began, the Franks had sought permission to immigrate to the United States. Otto Frank, Anne’s father, filled out the small mountain of required application forms and obtained supporting affidavits from the family’s relatives in Massachusetts. But that was not enough for those who zealously guarded America’s gates against refugees. In fact, in 1941 the Roosevelt administration even added a new restriction: no refugee with close relatives in Europe could come to the U.S., on the grounds that the Nazis might hold their relatives hostage in order to force the refugee to undertake espionage for Hitler.

That’s right: Anne Frank, Nazi spy.

In 1939, refugee advocates in Congress introduced the Wagner-Rogers bill, which would have admitted 20,000 refugee children from Germany outside the quota system. Anne and her sister Margot, as German citizens, could have been among those children.

President Roosevelt’s cousin, Laura Delano Houghteling, who was the wife of the U.S. commissioner of immigration, articulated the sentiment of many opponents of the bill when she remarked at a dinner party that “20,000 charming children would all too soon grow up into 20,000 ugly adults.” FDR himself refused to support the bill. By the spring of 1939, Wagner-Rogers was dead.

One year later, Roosevelt opened our country’s doors to non-Jewish British children to keep them safe from the German blitz. And an appeal by Pets magazine in 1940 resulted in several thousand offers to take in British purebred puppies endangered by the war. But there was no room for Jewish children.

A Play That Saved Lives

Jan de Hartog was determined to do what the president of the United States refused to do: shelter Jewish children from the Nazis.

Witnessing the horrors of the mass deportations, and with memories of the St. Louis tragedy still fresh in his mind, de Hartog set pen to paper and created “Schipper Naast God,” or “Skipper Next to God,” a play based on the voyage of the St. Louis, although with a different ending. In de Hartog’s play, a German ship with Jewish refugees is turned away from South America, so the skipper sails it to Long Island, where he beaches the ship in the midst of a yachting competition, forcing the yachtsmen to rescue the passengers.

“We performed the play especially around the Zuider Zee, where I knew the fishermen very well,” de Hartog later explained. “They were ideal hosts for Jewish children. In those troubled times, there was a great demand for families that would accept Jewish children and hide them. The fishermen were ideal because they were a closed society, but they had a problem because they were against the Jews ‘who had crucified Christ.’ They had to be convinced that…at this point their Christian duty was to give sanctuary to these persecuted Jews. The play was an instrument to try [to] bring that about. We were successful; a number of children were placed with the fishermen. After each performance, the audience and players entered into lively discussions which were really the main part of the whole performance.”

The size of the cast, however, became a problem: with seventeen actors, the performances might attract the Germans’ attention.

“So I learned the play by heart and reached the ideal of every playwright: I sat down in front of an audience and acted out all the parts myself,” de Hartog later explained. “I recited the whole play with appropriate facial expressions, looking this way and that, to make sure that everyone understood that it was a different character. I had a whale of a time. I did about three hundred of these performances. The manuscript had been destroyed because there were house searches, and it was decided that there should be no copy of the play available. So there I was, acting all the parts by myself.”

The exact number of children who were sheltered as a result of de Hartog’s play is not known. Altogether, an estimated 25,000-30,000 Dutch Jews were hidden with the help of the Dutch underground, and about two-thirds of them survived the Holocaust. More than 100,000 Dutch Jews were murdered in Auschwitz.

A Patriot’s Determination

With the Gestapo closing in, de Hartog fled the Netherlands and reached England in 1943. There he assisted a group of exiled Dutch sailors who aided the war effort by undertaking hazardous missions for the British military. De Hartog was later awarded Holland’s Cross of Merit in recognition of his service.

De Hartog’s love of the sea never diminished. At one point after the war, he and his wife made their home in a 90-foot barge they converted into a houseboat. They used the houseboat as a floating hospital to aid Dutch flood victims in 1953, an experience chronicled in the 1972 film “The Little Ark,” starring Theodore Bikel.

De Hartog gained fame as a playwright in the United States after the war, with his romantic comedy “The Fourposter.” It debuted on Broadway in 1951, starring the real-life married couple of Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn, ran for 632 performances, and earned a Tony Award for best play for the year. Subsequently de Hartog moved to Texas, where he taught playwriting at the University of Houston.

In the meantime, “Skipper Next to God” also made it to Broadway – and Hollywood. It was performed on Broadway in 1948, directed by Lee Strasberg and starring John Garfield. In 1953, “Skipper” was made into a movie.

The New York Times, reviewing the Broadway version, was not enthusiastic about “Skipper” as a play but argued that it “deserves to be produced” because of its “high-minded” purpose in showing that during the Holocaust years, “in America no one doubts that morally the Jews should be admitted, but everyone comfortably hides behind the letter of the law” in keeping them out.

Jan de Hartog, who passed away in 2002, was never recognized for risking his life to save Jewish children from the Nazis. The time has come for him to receive that long overdue recognition.